Dirty COW CVE-2016-5195

Why is it called Dirty COW?

COW stands for Copy-On-Write, and the exploit is so named because it’s a race condition that was found in the way the Linux kernel’s memory subsystem handled the copy-on-write breakage of private read-only memory mappings. An unprivileged local user could use this flaw to gain write access to otherwise read-only memory mappings and thus escalate their privileges on the system.[1]

Overview

Dirty COW is a private-escalation vulnerability in the Linux kernel that affects all Linux-based operating systems using older versions of the Linux kernel. The bug allows for local privilege escalation through the exploitation of a race condition in the implementation of the copy-on-write mechanism in the kernel’s memory-management subsystem. Because of the race condition, with the right timing, a local attacker can exploit the copy-on-write mechanism to turn a read-only mapping of a file into a writable mapping. Although it is a local privilege escalation, any installed application, or malicious code smuggled onto a machine, could gain root-level access and completely hijack the device, and so remote attackers could use it in conjunction with other exploits that allow remote execution of non-privileged code to achieve remote root access on a computer. The attack itself does not leave traces in the system log.[2]

History

The vulnerability has existed in the Linux kernel since version 2.6.22 which was released in September of 2007, and there is information about the bug being actively exploited since at least October of 2016.[2]

The vulnerability was discovered by security researcher Phil Oester. However, Linux kernel boss Linus Torvalds admits to having tried to fix the issue, unsuccessfully, in 2007, stating there were problems stemming from s390, an IBM instruction architecture. At that time the condition was difficult to trigger so he ended up leaving it alone. Since then, because of changes made to the linux kernel, the bug became far more easily exploitable.

A patch was produced in 2016 but did not fully address the issue and a revised patch was released on November 27, 2017, before public dissemination of the vulnerability. The vulnerability has been patched in Linux kernel versions 4.8.3, 4.7.9, 4.4.26 and newer.

Systems Affected

- Any Android device up to Android version 7 (Nougat)

- Routers

- Linux based servers

- Internet-of-Things / Embedded Linux devices

- Virtualization and cloud platforms (docker, AWS)

- Any Unix/Linux Operating systems (Ubuntu, Debian, Redhat)

Basically anything running any type of Linux based OS was vulnerable (and might still be if they haven’t been updated).

Use Cases

Due to the attack complexity, differentiating between legitimate use and an attack cannot be done easily, and for the most part the bug doesn’t leave any evidence in the logs, making detection difficult. The attack could be detected by comparing the size of the binary against the size of the original binary, if one knows which binary may have been altered.

As such though the dirty COW exploit has many perceived use cases and proof-of-concepts there is little evidence of it’s use in the wild. There is the ZNIU malware family that targets android devices through apps, which has been proven to use the dirty COW method to escalate privilege. Red Hat also stated it was aware of an exploit leveraging this technique in the wild, but the company has not shared any other information on the specifics of it.

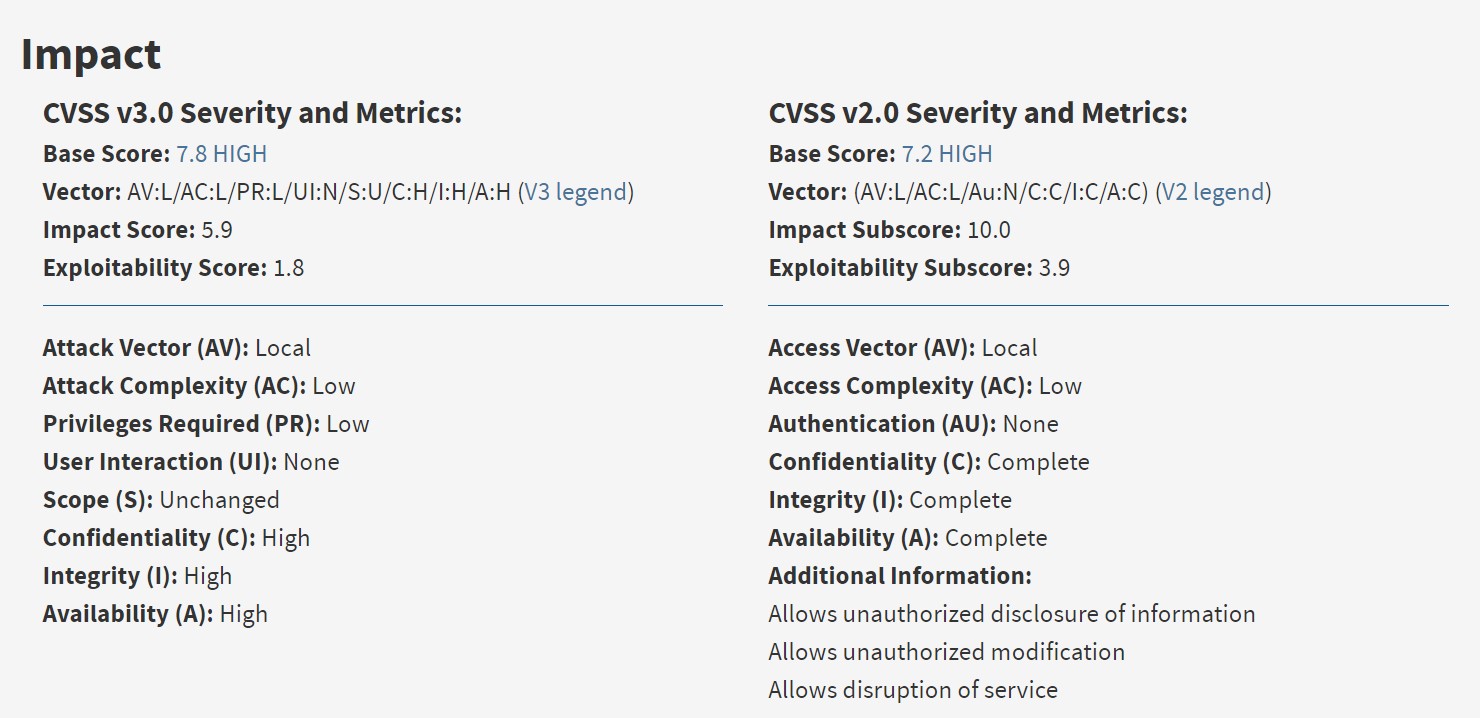

National Vulnerability Database

This is just a quick overview of the info available at the NVD site about this vulnerability.[3]

Due to the reliability of the privilege escalation and how many systems are vulnerable to it, it was given a high base score. Though the attacker does need to already have some access to the system in order to exploit it.

How it Works

Before, I mentioned some things that might be confusing depending on your knowledge of Linux, operating systems, and other processes. I’ll go into it further here. If you prefer videos I watched this one from LiveOverflow a few times to help my understanding of the exploit.

What is an Operating System Kernel?

The kernel is a computer program that at the base of a computer’s operating system and it has complete control over everything within the computer’s system. On most systems, it is one of the first programs loaded on start-up (after the bootloader), and it then handles the rest of start-up. It’s primary function during operation is to mediate access to the computer’s resources, meaning the CPU, RAM, and I/O devices.

Memory management

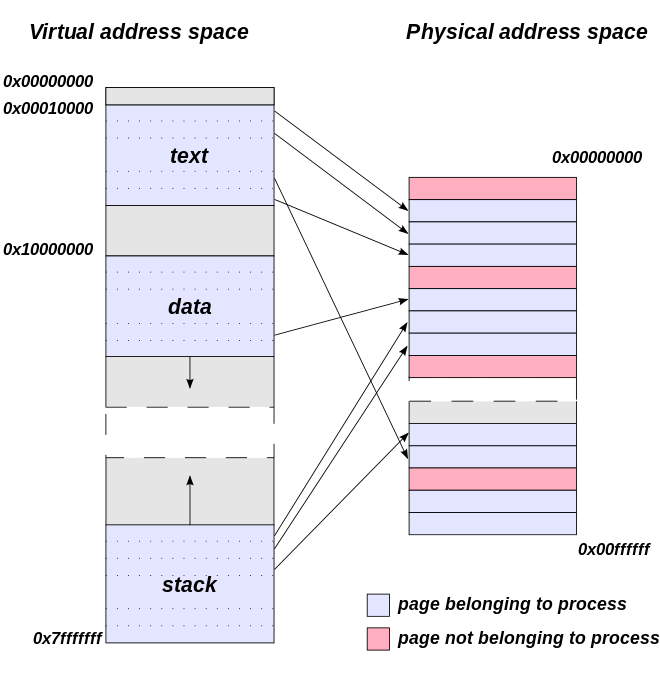

The kernel has full control of the system’s memory and allows processes to access this memory as they require it. The first step in doing this is virtual addressing, usually achieved by paging and/or segmentation. Virtual addressing allows the kernel to make a given virtual address appear to be the physical address. Virtual address spaces are different for different processes; so though two processes may appear to be accessing the same address, each process’s virtual address has been mapped to a different physical one. This allows every program to behave as if it is the only one (apart from the kernel) running and thus prevents applications from crashing each other.

On many systems, a program’s virtual address may refer to data which is not currently in memory (RAM). The layer of indirection provided by virtual addressing allows the operating system to use other data stores, like a hard drive, to store what would otherwise have to remain in memory. As a result, operating systems can allow programs to use more memory than the system has physically available. When a program needs data which is not currently in RAM, the CPU signals to the kernel that this has happened, and the kernel responds by writing the contents of an inactive (RAM) memory block to disk (if necessary) and replacing it with the data requested by the program. The program can then be resumed from the point where it was stopped. This scheme is generally known as demand paging. Alternatively if the file is requested for say read only, the kernel may map the virtual address to the hard disk, as reading from the disk is slower than memory, but copying the file into memory and then reading it may be slower than reading from the disk, and it means that less of the limited RAM memory is being used.

So the memory that the processes use is a logical address space that only exists for that process. From the operating system’s perspective it sees it in terms of pages. These pages are blocks of virtual memory that map to the physical memory. As far as the process is concerned this page is a section of the physical memory, and every byte is consecutive to the next. However the operating system has not provided a whole section of the physical memory like this, and areas of a processes virtual memory will map all over the physical memory. The kernel uses a translation table to determine what maps to what and which process can access it.

Copy-On-Write

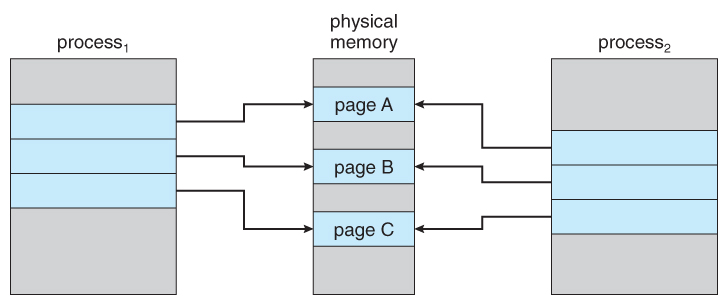

If a virtual memory page has the exact same data as another, the kernel can map them both to the same physical location, rather than use double the physical memory required to store the data. This page can be from a completely different process as well, so long as for a time they contain the same data. If all both programs can do is read from that memory location there are never any problems, because the data never changes.

When one process wants to modify that memory location then the kernel detects that a change is going to be made, which means that it is no longer the same between the two processes. So the kernel copies the unchanged data to another physical location and updates the translation table so that the process points to the new location instead, then writes the change to the new location. So the processes then point to two separate locations.

Private copy-on-write mapping can be done, and this means that updates to the mapping are not visible to other processes mapping the same file, and are not carried through to the underlying file.

Dirty Bit

A dirty bit is also called a modified bit, and it is a bit that is associated with a block of computer memory and indicates whether or not the corresponding block of memory has been modified. The dirty bit is set when the processor writes to (modifies) this memory block and indicates to the OS that its associated block of memory has been modified and has not been saved to storage yet. The OS does this because writing back to the disk memory is very slow, so the kernel tries to minimize the amount of writing back it has to do during operation and instead it caches or buffers the modified files. If a block of memory or a page is to be replaced in the RAM, its corresponding dirty bit is checked to see if the block needs to be written back to the disk memory before being replaced, if the dirty bit is not set then the copy can simply be removed because it’s the same as the disk version.

Linux ‘File’ System

The proc filesystem (procfs) is a special filesystem in Unix-like operating systems that presents information about processes and other system information in a hierarchical file-like structure, providing a standardized method for accessing process data held in the kernel. This is different from traditional tracing methods or direct access to kernel memory. Typically, it is mapped to a mount point named /proc at boot time. The proc file system acts as an interface to internal data structures in the kernel. It can be used to obtain information about the system and to change certain kernel parameters at runtime.

The Linux implementation includes a directory for each running process, including kernel processes, in directories named /proc/PID, where PID is the process number. Each directory contains information about one of the current processes.

The Linux kernel also extends this system to non–process-related data. So in Linux the /proc file system is a pseudo file system, and resources are managed as files. This means that in Linux a ‘file’ is really just something that you can read or write to; documents, directories, hard-drives, modems, keyboards, printers, are all treated like files. If you wanted to print something you could write to the printer ‘file’ which would result in the string being physically printed out onto a piece of paper. In this way /proc doesn’t contain files in the common sense, these ‘files’ refer to something more general. For this explanation it’s just important to recognize a ‘file’ as something that you can read or write to.

What is a Race Condition?

A race condition is an undesirable situation that occurs when a device or system attempts to perform two or more operations at the same time, but because of the nature of the device or system, the operations must be done in the proper sequence to be done correctly. [5]

The basic idea of the dirty COW race condition is that the program contains a code sequence that runs concurrently with another code sequence, say thread 1 and 2. Thread 1 requires temporary, exclusive access to a shared resource, but a timing window exists in which the shared resource can be modified by thread 2 before 1 has completed it’s operation.

In general for a race condition a code sequence may be in the form of a function call, a small number of instructions, a series of program invocations, etc. A race condition violates these properties, which are closely related:

- Exclusivity - the code sequence is given exclusive access to the shared resource, i.e., no other code sequence can modify properties of the shared resource before the original sequence has completed execution.

- Atomicity - the code sequence is behaviorally atomic, meaning no other thread or process can concurrently execute the same sequence of instructions (or a subset) on the same resource.

A race condition exists when an “interfering code sequence” can still access the shared resource, violating exclusivity. Programmers may assume that certain code sequences execute too quickly to be affected by an interfering code sequence; when they are not, this violates atomicity. For example, in c the single “x++” statement may appear atomic at the code layer, but it is actually non-atomic at the instruction layer, since it involves a read (the original value of x), followed by a computation (x+1), followed by a write (save the result to x).

For a simple example say you have two processes, and both are flipping the value of the same bit. So both processes should read the value, calculate the flipped value, then write the flipped value to the location. Normal operation would occur like in the table. One operation, then the other.

| Process 1 | Process 2 | Memory Value |

|---|---|---|

| Read value | 0 | |

| Flip value | 1 | |

| Read value | 1 | |

| Flip value | 0 |

Process 1 performs a bit flip, changing the memory value from 0 to 1. Process 2 then performs a bit flip and changes the memory value from 1 to 0. If a race condition occurred causing these two processes to overlap, the sequence could potentially look like this:

| Process 1 | Process 2 | Memory Value |

|---|---|---|

| Read value | 0 | |

| Read value | 0 | |

| Flip value | 1 | |

| Flip value | 1 |

In this example, the bit has a final value of 1 when its value should be 0. This occurs because Process 2 is unaware that Process 1 is performing a simultaneous bit flip.

Dirty Copy-On-Write

The dirty COW exploit uses all of these processes and aspects of the Linux kernel to exploit the fact that the copy-on-write facility, and the virtual memory release facility do not check whether anything else is operating on the memory space. Thus allowing the attacker to force the two processes of the kernel, the copy-on-write and the one writing to the memory, out of sync.

So how were all these processes exploited?

The steps of the dirty COW exploit when run under normal conditions should not result in any issues. It starts by requesting to read a file owned by root. The process has read only permission on that file, and when it does so it purposefully requests that the file not be copied into RAM, but that the translation table map directly to the disk where the process can read the file from. It also requests that the system make this mapping private. Now if the process were to try to write to this memory segment, because it is privately mapped, that will trigger a copy of the file from disk to be created, the translation table will be updated, and then the copy modified. Then it releases that virtual memory space, telling the kernel that it no longer needs the file. The kernel checks the dirty bit, looks back to the disk, sees that there are no write permissions, and throws away the copy without storing it.

But what about if this process is broken into two parallel threads of code?

So first you open any file that you have read access to on the system, in doing this it privately maps the file into a specific place in the virtual memory that is mapped directly to the disk rather than a copy of the file in RAM.

Then you create two threads to run in parallel.

The first thread that is created looks to the specific memory area that the file was mapped to and it tells the kernel that it no longer needs that file, it can release the memory. The specific command allows the system to access the data after it has been released, but it requires the system to repopulate the memory contents from the underlying mapped file. So it leaves the system a way to get the data from the disk again.

The second thread is opening the /proc/self/mem file. Now in Linux’s pseudo filesystem:

- /proc - gives information about processes

- /proc/self - refers to a special ‘file’ provided for the current process to access and has information about the current process. Each process has their own /proc/self

- /proc/self/mem - a ‘file’ that is a representation of the current process’s memory

So theoretically you could read your own processes memory by reading from this ‘file’

Thread 2 writes to this file which is what triggers the copy of the file to be made in memory, and the modifications that the thread requests are made to that copy. The private mapping means the process can see the changes, but nothing is being written to the real underlying file. Using normal seek and write operations, it overwrites part of its own memory that’s mapped to the root-owned executable (the file opened in the beginning). [7]

Then these two threads are run in parallel in loops; open → copy → write, and release memory.

So what should happen is that they would behave as though they were a part of the same thread and the two processes will take enough time that they will sort of take turns.

| Don’t Need Thread | proc/self/mem Thread |

|---|---|

| don’t need(mapped file) | |

| write(mapped file) | |

| don’t need(mapped file) | |

| write(mapped file) | |

| don’t need(mapped file) | |

| write(mapped file) |

But, if these two threads are sped up so that the operations occurring multiple times a second, then you create a race. The two threads need to keep up with each other in order to remain interwoven. When you do this over and over again very quickly, you can create this edge case where the timing doesn’t work out and the instructions for one thread start exectuing before the other has completed.

| Don’t Need Thread | proc/self/mem Thread |

|---|---|

| don’t need(mapped file) | write(mapped file) |

| don’t need(mapped file) | write(mapped file) |

| write(mapped file) | |

| write(mapped file) | |

| don’t need(mapped file) | |

| write(mapped file) |

Now if this happens it tricks the kernel into writing to the underlying file.

Instead of the process following proper procedure, what happens is the kernel goes to create the copy, but this takes time, enough time that the don’t need thread that is running in parallel already told the kernel to throw the copy away, so it gets deleted. When the kernel goes to make the modification to the copy of the file in RAM it doesn’t find the copy, instead it still has the mapping to the original disk file, but it doesn’t realize that this is not the copy, because there was no error in this procedure, and it modifies the real disk file because the kernel has permission to modify anything in the system. [6]

In summary:

Normal Situation:

- You request to read from a file owned by root

- Page table maps to disk location

- You request write

- Copy created

- Page table updates to point to copy

- You write

- Copy gets modified

- Request to release memory space containing copy

- File isn’t saved because you have read only privilege

With Race Condition:

- You request to read from a file owned by root

- Page table maps to disk location

- You request write

- Copy being created

- Before the copy is done the Don’t Need in the other thread throws away the copy

- Memory Manager still has original mapping, thus the write is applied to the original file

The overall result being that a file on disk that an attacker does not have permission to write is changed. In this way attackers could access a file on the system insert shell code, run that file and get themselves a root shell, or anything else that they want from the system.

The Demo

There are multiple proof of concepts available here. The code used in the demonstration is from the pokemon.c exploit available here. The box that I’m gaining access to is from a CTF assignment that a professor of mine set up.

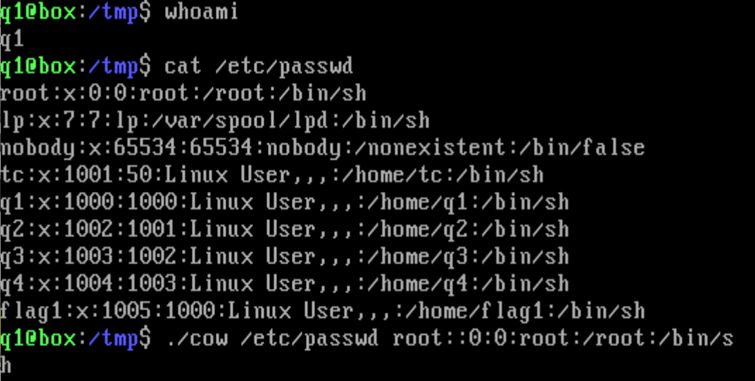

So here we see that I’m signed in as user q1, now I forgot to show this but since it’s a capture the flag challenge you can assume that I didn’t just have access to the flag files. The passwd file has the root users info in the first line. Each line of the passwd file is organized like:

username:password:User ID:Group ID:User ID Info:Home Directory:Command/Shell

If I change that line and remove the x in the password position then the system will read that root does not require a password.

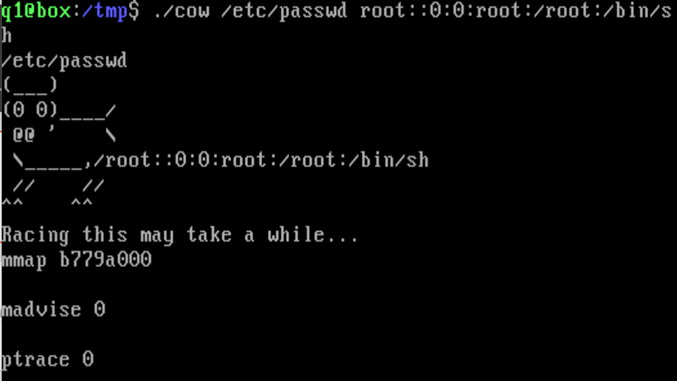

So I’ve written the code and compiled it, and give the exploit the passwd file and new string without x.

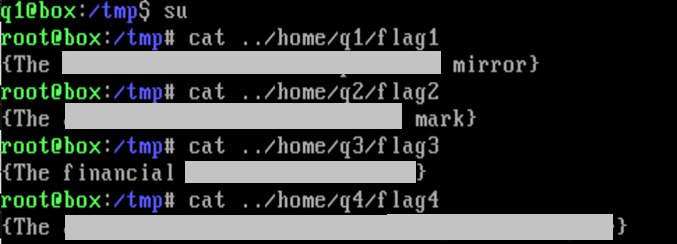

Then once that finishes I use the super user command and I’m now the root user and can open all the flags.

Though I did redact the flag strings in case any of the prof’s future students were looking to get them that easy. ![]()

The Patch

From the documentation

To fix it, we introduce a new internal FOLL_COW flag to mark the “yes, we already did a COW” rather than play racy games with FOLL_WRITE that is very fundamental, and then use the pte dirty flag to validate that the FOLL_COW flag is still valid.

Essentially they added flags so that the system knows that the COW has been completed before releasing the memory space.

References

[1] https://bugzilla.redhat.com/show_bug.cgi?id=1384344#[2] https://www.zdnet.com/article/the-dirty-cow-linux-security-bug-moos/

[3] https://nvd.nist.gov/vuln/detail/CVE-2016-5195#vulnCurrentDescriptionTitle

[4] http://man7.org/linux/man-pages/man2/mmap.2.html

[5] http://cwe.mitre.org/data/definitions/362.html

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kEsshExn7aE

[7] https://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/10/21/linux_privilege_escalation_hole/

[8] https://git.kernel.org/pub/scm/linux/kernel/git/torvalds/linux.git/commit/?id=19be0eaffa3ac7d8eb6784ad9bdbc7d67ed8e619

dirty COW POC code: https://github.com/dirtycow/dirtycow.github.io/wiki/PoCs